The Greenhouse Effect and Global Warming

Although seasons come and go, on average the earth’s climate is very steady. To maintain this stability, the earth must radiate thermal energy—electromagnetic waves—back into space at exactly the same average rate that it receives energy from the sun. Because the earth is much cooler than the sun, its thermal radiation is long-wavelength infrared radiation that we cannot see. A straightforward calculation using Stefan's law finds that the average temperature of the earth should be –18°C, or 0°F, for the incoming and outgoing radiation to lie in balance.

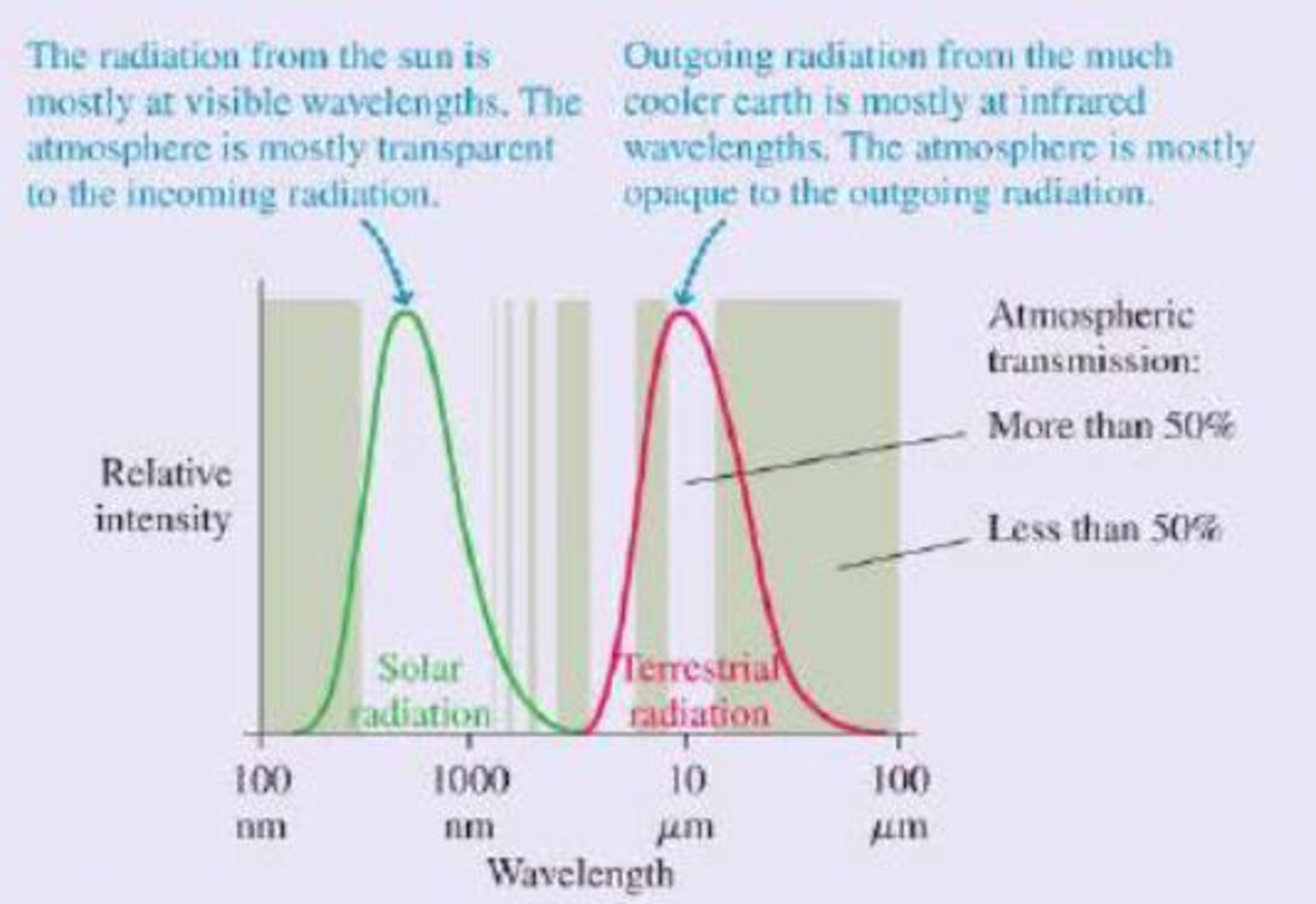

This result is clearly not correct; at this temperature, the entire earth would be covered in snow and ice. The measured global average temperature is actually a balmier 15°C, or 59°F. The straightforward calculation fails because it neglects to consider the earth’s atmosphere. At visible wavelengths, as the figure shows, the atmosphere has a wide “window” of transparency, but this is not true at the infrared wavelengths of the earth’s thermal radiation. The atmosphere lets in the visible radiation from the sun, but the outgoing thermal radiation from the earth sees a much smaller “window.” Most of this radiation is absorbed in the atmosphere.

Thermal radiation curves for the sun and the earth. The shaded bands show regions for which the atmosphere is transparent (no shading) or opaque (shaded) to electromagnetic radiation.

Because it’s easier for visible radiant energy to get in than for infrared to get out, the earth is warmer than it would be without the atmosphere. The additional warming of the earth’s surface because of the atmosphere is called the greenhouse effect. The greenhouse effect is a natural part of the earth’s physics; it has nothing to do with human activities, although it’s doubtful any advanced life forms would have evolved without it.

The atmospheric gases most responsible for the greenhouse effect are carbon dioxide and water vapor, both strong absorbers of infrared radiation. These greenhouse gases are of concern today because humans, through the burning of fossil fuels (oil, coal, and natural gas), are rapidly increasing the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. Preserved air samples show that carbon dioxide made up 0.027% of the atmosphere before the industrial revolution. In the last 150 years, human activities have increased the amount of carbon dioxide by nearly 50%, to about 0.040%. By 2050, the carbon dioxide concentration will likely increase to 0.054%, double the pre-industrial value, unless the use of fossil fuels is substantially reduced.

Carbon dioxide is a powerful absorber of infrared radiation. And good absorbers are also good emitters. The carbon dioxide in the atmosphere radiates energy back to the surface of the earth, warming it. Increasing the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere means more radiation: this increases the average surface temperature of the earth. The net result is global warming.

There is strong evidence that (he earth has warmed nearly 1°C in the last 100 years because of increased greenhouse gases. What happens next? Climate scientists, using sophisticated models of the earth’s atmosphere and oceans, calculate that a doubling of the carbon dioxide concentration will likely increase the earth’s average temperature by an additional 2°C (≈ 3°F) to 6°C (≈9°F) There is some uncertainty in these calculations; the earth is a large and complex system. Perhaps the earth will get cloudier as the temperature increases, moderating the increase. Or perhaps the arctic ice cap will melt, making the earth less reflective and leading to an even more dramatic

But the basic physics that leads to the greenhouse effect, and to global warming, is quite straightforward. Carbon dioxide in the atmosphere keeps the earth warm; more carbon dioxide will make it warmer. How much warmer? That’s an important question, one that many scientists around the world are attempting to answer with ongoing research. But large or small, change is coming. Global warming is one of the most serious challenges facing scientists, engineers, and all citizens in the 21st century.

The following questions are related to the passage “The Greenhouse Effect and Global Warming” on the previous page.

The intensity of sunlight at the top of the earth’s atmosphere is approximately 1400 W/m2. Mars is about 1.5 times as far from the sun as the earth. What is the approximate intensity of sunlight at the top of Mar’s atmosphere?

- A. 930 W/m2

- B. 620 W/m2

- C. 410 W/m2

- D. 280 W/m2

Want to see the full answer?

Check out a sample textbook solution

Chapter P Solutions

College Physics: A Strategic Approach (3rd Edition)

Additional Science Textbook Solutions

Introductory Chemistry (6th Edition)

Human Biology: Concepts and Current Issues (8th Edition)

Microbiology with Diseases by Body System (5th Edition)

Campbell Biology (11th Edition)

Chemistry (7th Edition)

Campbell Essential Biology with Physiology (5th Edition)

- 5.48 ⚫ A flat (unbanked) curve on a highway has a radius of 170.0 m. A car rounds the curve at a speed of 25.0 m/s. (a) What is the minimum coefficient of static friction that will prevent sliding? (b) Suppose that the highway is icy and the coefficient of static friction between the tires and pavement is only one-third of what you found in part (a). What should be the maximum speed of the car so that it can round the curve safely?arrow_forward5.77 A block with mass m₁ is placed on an inclined plane with slope angle a and is connected to a hanging block with mass m₂ by a cord passing over a small, frictionless pulley (Fig. P5.74). The coef- ficient of static friction is μs, and the coefficient of kinetic friction is Mk. (a) Find the value of m₂ for which the block of mass m₁ moves up the plane at constant speed once it is set in motion. (b) Find the value of m2 for which the block of mass m₁ moves down the plane at constant speed once it is set in motion. (c) For what range of values of m₂ will the blocks remain at rest if they are released from rest?arrow_forward5.78 .. DATA BIO The Flying Leap of a Flea. High-speed motion pictures (3500 frames/second) of a jumping 210 μg flea yielded the data to plot the flea's acceleration as a function of time, as shown in Fig. P5.78. (See "The Flying Leap of the Flea," by M. Rothschild et al., Scientific American, November 1973.) This flea was about 2 mm long and jumped at a nearly vertical takeoff angle. Using the graph, (a) find the initial net external force on the flea. How does it compare to the flea's weight? (b) Find the maximum net external force on this jump- ing flea. When does this maximum force occur? (c) Use the graph to find the flea's maximum speed. Figure P5.78 150 a/g 100 50 1.0 1.5 0.5 Time (ms)arrow_forward

- 5.4 ⚫ BIO Injuries to the Spinal Column. In the treatment of spine injuries, it is often necessary to provide tension along the spi- nal column to stretch the backbone. One device for doing this is the Stryker frame (Fig. E5.4a, next page). A weight W is attached to the patient (sometimes around a neck collar, Fig. E5.4b), and fric- tion between the person's body and the bed prevents sliding. (a) If the coefficient of static friction between a 78.5 kg patient's body and the bed is 0.75, what is the maximum traction force along the spi- nal column that W can provide without causing the patient to slide? (b) Under the conditions of maximum traction, what is the tension in each cable attached to the neck collar? Figure E5.4 (a) (b) W 65° 65°arrow_forwardThe correct answers are a) 367 hours, b) 7.42*10^9 Bq, c) 1.10*10^10 Bq, and d) 7.42*10^9 Bq. Yes I am positve they are correct. Please dont make any math errors to force it to fit. Please dont act like other solutiosn where you vaugley state soemthing and then go thus, *correct answer*. I really want to learn how to properly solve this please.arrow_forwardI. How many significant figures are in the following: 1. 493 = 3 2. .0005 = | 3. 1,000,101 4. 5.00 5. 2.1 × 106 6. 1,000 7. 52.098 8. 0.00008550 9. 21 10.1nx=8.817arrow_forward

College PhysicsPhysicsISBN:9781938168000Author:Paul Peter Urone, Roger HinrichsPublisher:OpenStax College

College PhysicsPhysicsISBN:9781938168000Author:Paul Peter Urone, Roger HinrichsPublisher:OpenStax College Physics for Scientists and EngineersPhysicsISBN:9781337553278Author:Raymond A. Serway, John W. JewettPublisher:Cengage Learning

Physics for Scientists and EngineersPhysicsISBN:9781337553278Author:Raymond A. Serway, John W. JewettPublisher:Cengage Learning Physics for Scientists and Engineers with Modern ...PhysicsISBN:9781337553292Author:Raymond A. Serway, John W. JewettPublisher:Cengage Learning

Physics for Scientists and Engineers with Modern ...PhysicsISBN:9781337553292Author:Raymond A. Serway, John W. JewettPublisher:Cengage Learning

Glencoe Physics: Principles and Problems, Student...PhysicsISBN:9780078807213Author:Paul W. ZitzewitzPublisher:Glencoe/McGraw-Hill

Glencoe Physics: Principles and Problems, Student...PhysicsISBN:9780078807213Author:Paul W. ZitzewitzPublisher:Glencoe/McGraw-Hill AstronomyPhysicsISBN:9781938168284Author:Andrew Fraknoi; David Morrison; Sidney C. WolffPublisher:OpenStax

AstronomyPhysicsISBN:9781938168284Author:Andrew Fraknoi; David Morrison; Sidney C. WolffPublisher:OpenStax