Concept explainers

Waves in the Earth and the Ocean

In December 2004, a large earthquake off the coast of Indonesia produced a devastating water wave, called a tsunami, that caused tremendous destruction thousands of miles away from the earthquake's epicenter. The tsunami was a dramatic illustration of the energy carried by waves.

It was also a call to action. Many of the communities hardest hit by the tsunami were struck hours after the waves were generated, long after seismic waves from the earthquake that passed through the earth had been detected al distant recording stations, long after the possibility of a tsunami was first discussed. With better detection and more accurate models of how a tsunami is formed and how a tsunami propagates, the affected communities could have received advance warning. The study of physics may seem an abstract undertaking with few practical applications, but on this day a better scientific understanding of these waves could have averted tragedy.

Let’s use our knowledge of waves to explore the properties of a tsunami. In Chapter 15, we saw that a vigorous shake of one end of a rope causes a pulse to travel

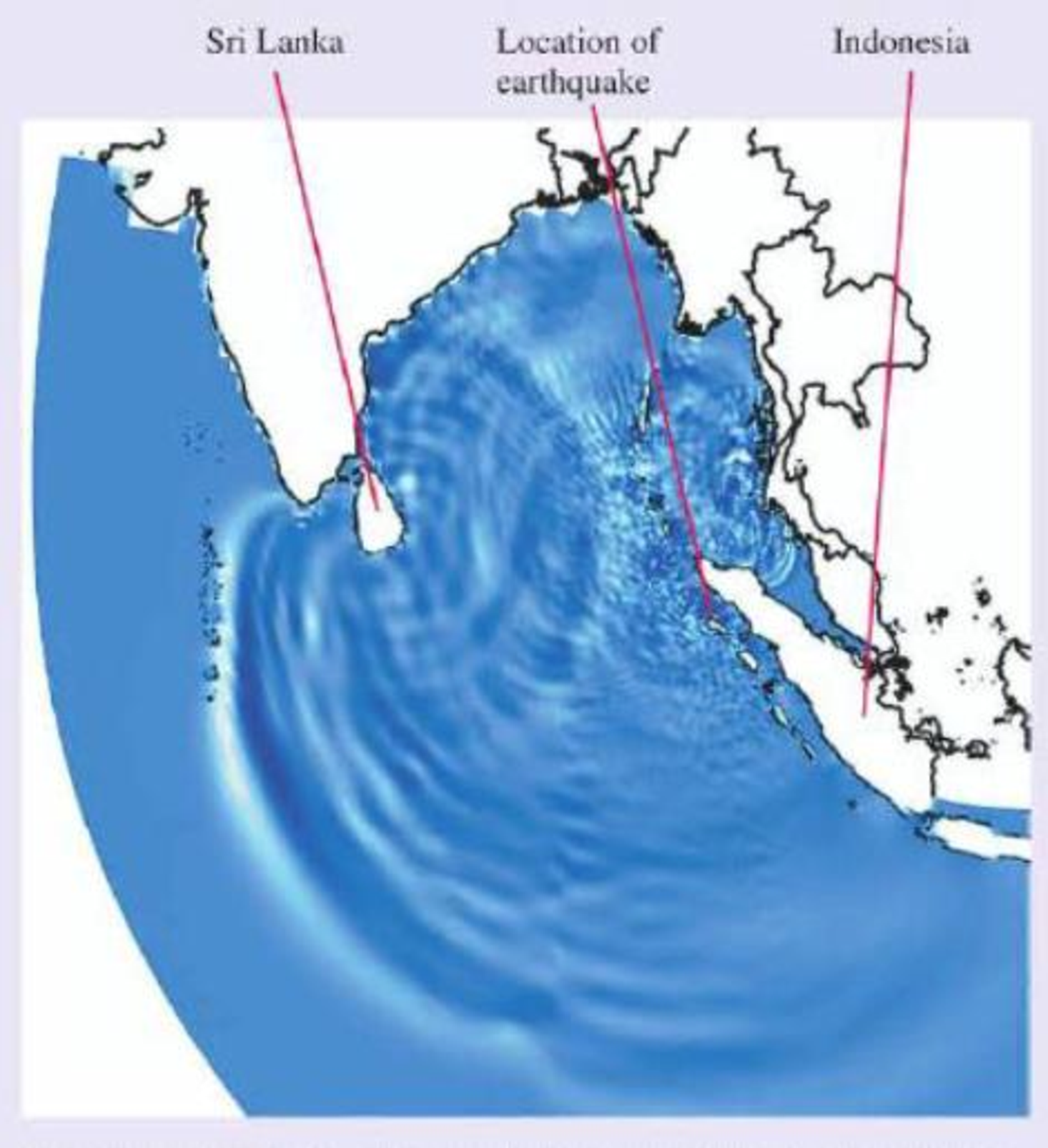

One frame from a computer simulation of the Indian Ocean tsunami three hours after the earthquake that produced it. The disturbance propagating outward from the earthquake is clearly seen, as are wave reflections from the island of Sri Lanka.

along it, carrying energy as it goes. The earthquake that produced the Indian Ocean tsunami of 2004 caused a sudden upward displacement of the seafloor that produced a corresponding rise in the surface of the ocean. This was the disturbance that produced the tsunami, very much like a quick shake on the end of a rope. The resulting wave propagated through the ocean, as we see in the figure.

This simulation of the tsunami looks much like the ripples that spread when you drop a pebble into a pond. But there is a big difference—the scale. The fact that you can see the individual waves on this diagram that spans 5000 km is quite revealing. To show up so clearly, the individual wave pulses must be very wide—up to hundreds of kilometers from front to back.

A tsunami is actually a “shallow water wave,” even in the deep ocean, because the depth of the ocean is much less than the width of the wave. Consequently, a tsunami travels differently than normal ocean waves. In Chapter 15 we learned that wave speeds are fixed by the properties of the medium. That is true for normal ocean waves, but the great width of the wave causes a tsunami to “feel the bottom.” Its wave speed is determined by the depth of the ocean: The greater the depth, the greater the speed. In the deep ocean, a tsunami travels at hundreds of kilometers per hour, much faster than a typical ocean wave. Near shore, as the ocean depth decreases, so docs the speed of the wave.

The height of the tsunami in the open ocean was about half a meter. Why should such a small wave—one that ships didn't even notice as it passed—be so fearsome? Again, it's the width of the wave that matters. Because a tsunami is the wave motion of a considerable mass of water, great energy is involved. As the front of a tsunami wave nears shore, its speed decreases, and the back of the wave moves faster than the front. Consequently, the width decreases. The water begins to pile up, and the wave dramatically increases in height.

The Indian Ocean tsunami had a height of up to 15 m when it reached shore, with a width of up to several kilometers. This tremendous mass of water was still moving at high speed, giving it a great deal of energy. A tsunami reaching the shore isn’t like a typical wave that breaks and crashes. It is a kilometers-wide wall of water that moves onto the shore and just keeps on coming. In many places, the water reached 2 km inland.

The impact of the Indian Ocean tsunami was devastating, but it was the first tsunami for which scientists were able to use satellites and ocean sensors to make planet-wide measurements. An analysis of the data has helped us better understand the physics of these ocean waves. We won’t be able to stop future tsunamis, but with a better knowledge of how they are formed and how they travel, we will be better able to warn people to get out of their way.

The following questions are related to the passage“Waves in the Earth and the Ocean ” on the previous page.

Rank from fastest to slowest the following waves according to their speed of propagation:

A. An earthquake wave

B. A tsunami

C. A sound wave in air

D. A light wave

Want to see the full answer?

Check out a sample textbook solution

Chapter P Solutions

College Physics: A Strategic Approach (3rd Edition)

Additional Science Textbook Solutions

Anatomy & Physiology (6th Edition)

Microbiology: An Introduction

Campbell Essential Biology (7th Edition)

Chemistry: An Introduction to General, Organic, and Biological Chemistry (13th Edition)

Organic Chemistry (8th Edition)

Cosmic Perspective Fundamentals

- RT = 4.7E-30 18V IT = 2.3E-3A+ 12 38Ω ли 56Ω ли r5 27Ω ли r3 28Ω r4 > 75Ω r6 600 0.343V 75.8A Now figure out how much current in going through the r4 resistor. |4 = unit And then use that current to find the voltage drop across the r resistor. V4 = unitarrow_forward7 Find the volume inside the cone z² = x²+y², above the (x, y) plane, and between the spheres x²+y²+z² = 1 and x² + y²+z² = 4. Hint: use spherical polar coordinates.arrow_forwardганм Two long, straight wires are oriented perpendicular to the page, as shown in the figure(Figure 1). The current in one wire is I₁ = 3.0 A, pointing into the page, and the current in the other wire is 12 4.0 A, pointing out of the page. = Find the magnitude and direction of the net magnetic field at point P. Express your answer using two significant figures. VO ΜΕ ΑΣΦ ? Figure P 5.0 cm 5.0 cm ₁ = 3.0 A 12 = 4.0 A B: μΤ You have already submitted this answer. Enter a new answer. No credit lost. Try again. Submit Previous Answers Request Answer 1 of 1 Part B X Express your answer using two significant figures. ΜΕ ΑΣΦ 0 = 0 ? below the dashed line to the right P You have already submitted this answer. Enter a new answer. No credit lost. Try again.arrow_forward

Physics for Scientists and Engineers, Technology ...PhysicsISBN:9781305116399Author:Raymond A. Serway, John W. JewettPublisher:Cengage Learning

Physics for Scientists and Engineers, Technology ...PhysicsISBN:9781305116399Author:Raymond A. Serway, John W. JewettPublisher:Cengage Learning College PhysicsPhysicsISBN:9781938168000Author:Paul Peter Urone, Roger HinrichsPublisher:OpenStax College

College PhysicsPhysicsISBN:9781938168000Author:Paul Peter Urone, Roger HinrichsPublisher:OpenStax College An Introduction to Physical SciencePhysicsISBN:9781305079137Author:James Shipman, Jerry D. Wilson, Charles A. Higgins, Omar TorresPublisher:Cengage Learning

An Introduction to Physical SciencePhysicsISBN:9781305079137Author:James Shipman, Jerry D. Wilson, Charles A. Higgins, Omar TorresPublisher:Cengage Learning Principles of Physics: A Calculus-Based TextPhysicsISBN:9781133104261Author:Raymond A. Serway, John W. JewettPublisher:Cengage Learning

Principles of Physics: A Calculus-Based TextPhysicsISBN:9781133104261Author:Raymond A. Serway, John W. JewettPublisher:Cengage Learning Glencoe Physics: Principles and Problems, Student...PhysicsISBN:9780078807213Author:Paul W. ZitzewitzPublisher:Glencoe/McGraw-Hill

Glencoe Physics: Principles and Problems, Student...PhysicsISBN:9780078807213Author:Paul W. ZitzewitzPublisher:Glencoe/McGraw-Hill Physics for Scientists and Engineers: Foundations...PhysicsISBN:9781133939146Author:Katz, Debora M.Publisher:Cengage Learning

Physics for Scientists and Engineers: Foundations...PhysicsISBN:9781133939146Author:Katz, Debora M.Publisher:Cengage Learning