Concept explainers

Size and Life

Physicists look for simple models and general principles that underlie and explain diverse physical phenomena. In the first 13 chapters of this textbook, you’ve seen that just a handful of general principles and laws can be used to solve a wide range of problems. Can this approach have any relevance to a subject like biology? It may seem surprising, but there are general 'laws of biology“’ that apply, with quantitative accuracy, to organisms as diverse as elephants and mice.

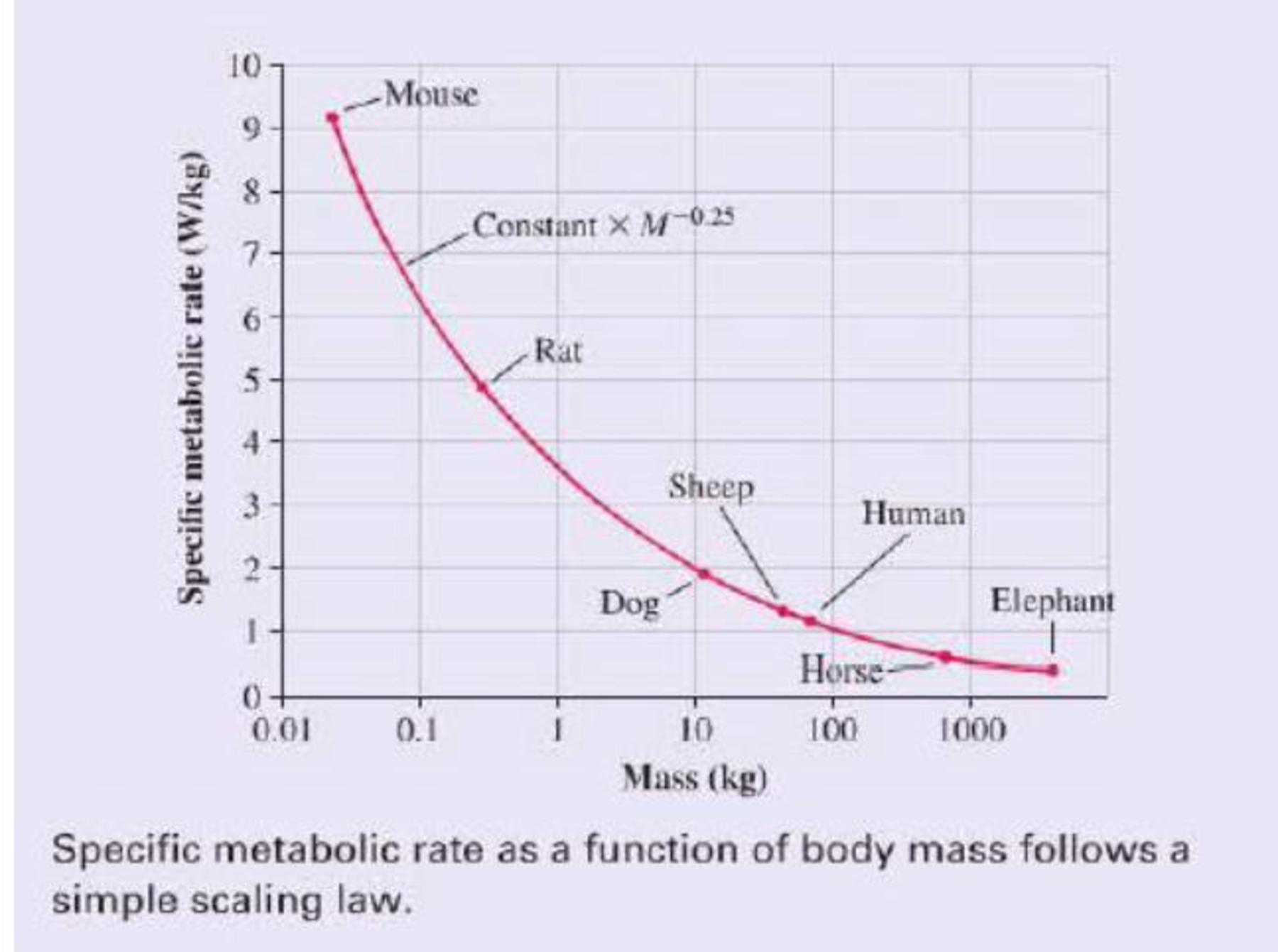

Let’s look at an example. An elephant uses more metabolic power than a mouse. This is not surprising, as an elephant is much bigger. But recasting the data shows an interesting trend. When we looked at the energy required to raise the temperature of different substances, we considered specific heat. The “specific” meant that we considered the heat required for 1 kilogram. For animals, rather than metabolic rate, we can look at the specific metabolic rate, the metabolic power used per kilogram of tissue. If we factor out the mass difference between a mouse and an elephant, are their specific metabolic powers the same?

In fact, the specific metabolic rate varies quite a bit among mammals, as the graph of specific metabolic rate versus mass shows. But there is an interesting trend: All of the data points lie on a single smooth curve. In other words, there really is a biological law we can use to predict a mammal’s metabolic rate knowing only its mass M. In particular, the specific metabolic rate is proportional to M –0.25. Because a 4000 kg elephant is 160,000 times more massive than a 25 g mouse, the mouse’s specific metabolic power is (160,000)0.25 = 20 times that of the elephant. A law that shows how a property scales with the size of a system is called a scaling law.

A similar scaling law holds for birds, reptiles, and even bacteria. Why should a single simple relationship hold true for organisms that range in size from a single cell to a 100 ton blue whale? Interestingly, no one knows for sure. It is a matter of current research to find out just what this and other scaling laws tell us about the nature of life.

Perhaps the metabolic-power scaling law is a result of

If heat dissipation were the only factor limiting metabolism, we can show that the specific metabolic rate should scale as M–0.33quite different from the M–0.25 scaling observed. Clearly, another factor is at work. Exactly what underlies the M–0.25 scaling is still a matter of debate, but some recent analysis suggests the scaling is due to limitations not of heat transfer but of fluid flow. Cells in mice, elephants, and all mammals receive nutrients and oxygen for metabolism from the bloodstream. Because the minimum size of a capillary is about the same for all mammals, the structure of the circulatory system must vary from animal to animal. The human aorta has a diameter of about 1 inch; in a mouse, the diameter is approximately l/20th of this. Thus a mouse has fewer levels of branching to smaller and smaller blood vessels as we move from the aorta to the capillaries. The smaller blood vessels in mice mean that viscosity is more of a factor throughout the circulatory system. The circulatory system of a mouse is quite different from that of ail elephant.

A model of specific metabolic rate based on blood-flow limitations predicts a M–0.25 law, exactly as observed. The model also makes other testable predictions. For example, the model predicts that the smallest possible mammal should have a body mass of about 1 gram—exactly the size of the smallest shrew. Even smaller animals have different types of circulatory' systems; in the smallest animals, nutrient transport is by diffusion alone. But the model can be extended to predict that the specific metabolic rate for these animals will follow a scaling law similar to that for mammals, exactly as observed. It is too soon to know if this model will ultimately prove to be correct, but it’s indisputable that there are large-scale regularities in biology that follow mathematical relationships based on the laws of physics.

The following questions are related to the passage "Size and Life" on the previous page.

All other things being equal, species that inhabit cold climates tend to be larger than related species that inhabit hot climates. For instance, the Alaskan hare is the largest North American hare, with a typical mass of 5.0 kg, double that of a jackrabbit. A likely explanation is that

- A. Larger animals have more blood flow, allowing for better thermoregulation.

- B. Larger animals need less food to survive than smaller animals.

- C. Larger animals have larger blood volumes than smaller animals.

- D. Larger animals lose heat less quickly than smaller animals.

Want to see the full answer?

Check out a sample textbook solution

Chapter P Solutions

College Physics: A Strategic Approach (3rd Edition)

Additional Science Textbook Solutions

Concepts of Genetics (12th Edition)

Applications and Investigations in Earth Science (9th Edition)

Cosmic Perspective Fundamentals

Genetic Analysis: An Integrated Approach (3rd Edition)

Chemistry: The Central Science (14th Edition)

Human Anatomy & Physiology (2nd Edition)

- 3. In a rotating vertical cylinder (Rotor-ride) a rider finds herself pressed with her back to the rotating wall. Which is the correct free-body diagram for her? (a) (b) (c) (d) (e)arrow_forward8. A roller coaster rounds the bottom of a circular loop at a nearly constant speed. At this point the net force on the coaster cart is (a) zero. (b) directed upward. (c) directed downward. (d) Cannot tell without knowing the exact speed.arrow_forward5. While driving fast around a sharp right turn, you find yourself pressing against the left car door. What is happening? (a) Centrifugal force is pushing you into the door. (b) The door is exerting a rightward force on you. (c) Both of the above. (d) Neither of the above.arrow_forward

- 7. You are flung sideways when your car travels around a sharp curve because (a) you tend to continue moving in a straight line. (b) there is a centrifugal force acting on you. (c) the car exerts an outward force on you. (d) of gravity.arrow_forward1. A 50-N crate sits on a horizontal floor where the coefficient of static friction between the crate and the floor is 0.50. A 20-N force is applied to the crate acting to the right. What is the resulting static friction force acting on the crate? (a) 20 N to the right. (b) 20 N to the left. (c) 25 N to the right. (d) 25 N to the left. (e) None of the above; the crate starts to move.arrow_forward3. The problem that shall not be named. m A (a) A block of mass m = 1 kg, sits on an incline that has an angle 0. Find the coefficient of static friction by analyzing the system at imminent motion. (hint: static friction will equal the maximum value) (b) A block of mass m = 1kg made of a different material, slides down an incline that has an angle 0 = 45 degrees. If the coefficient of kinetic friction increases is μ = 0.5 what is the acceleration of the block? karrow_forward

- 2. Which of the following point towards the center of the circle in uniform circular motion? (a) Acceleration. (b) Velocity, acceleration, net force. (c) Velocity, acceleration. (d) Velocity, net force. (e) Acceleration, net force.arrow_forwardProblem 1. (20 pts) The third and fourth stages of a rocket are coastin in space with a velocity of 18 000 km/h when a smal explosive charge between the stages separate them. Immediately after separation the fourth stag has increased its velocity to v4 = 18 060 km/h. Wha is the corresponding velocity v3 of the third stage At separation the third and fourth stages hav masses of 400 and 200 kg, respectively. 3rd stage 4th stagearrow_forwardMany experts giving wrong answer of this question. please attempt when you 100% sure . Otherwise i will give unhelpful.arrow_forward

- Determine the shear and moment diagram for the beam shown in Fig.1. A 2 N/m 10 N 8 N 6 m B 4m Fig.1 40 Nm Steps: 1) Determine the reactions at the fixed support (RA and MA) (illustrated in Fig 1.1) 2) Draw the free body diagram on the first imaginary cut (fig. 1.2), and determine V and M. 3) Draw the free body diagram on the second imaginary cut (fig. 1.3), and determine V and M. 4) Draw the shear and moment diagramarrow_forwardConsidering the cross-sectional area shown in Fig.2: 1. Determine the coordinate y of the centroid G (0, ỹ). 2. Determine the moment of inertia (I). 3. Determine the moment of inertia (Ir) (with r passing through G and r//x (// parallel). 4 cm 28 cm G3+ G 4 cm y 12 cm 4 cm 24 cm xarrow_forwardI need help understanding 7.arrow_forward

Physics for Scientists and Engineers: Foundations...PhysicsISBN:9781133939146Author:Katz, Debora M.Publisher:Cengage Learning

Physics for Scientists and Engineers: Foundations...PhysicsISBN:9781133939146Author:Katz, Debora M.Publisher:Cengage Learning University Physics Volume 1PhysicsISBN:9781938168277Author:William Moebs, Samuel J. Ling, Jeff SannyPublisher:OpenStax - Rice University

University Physics Volume 1PhysicsISBN:9781938168277Author:William Moebs, Samuel J. Ling, Jeff SannyPublisher:OpenStax - Rice University Physics for Scientists and Engineers, Technology ...PhysicsISBN:9781305116399Author:Raymond A. Serway, John W. JewettPublisher:Cengage Learning

Physics for Scientists and Engineers, Technology ...PhysicsISBN:9781305116399Author:Raymond A. Serway, John W. JewettPublisher:Cengage Learning Physics for Scientists and EngineersPhysicsISBN:9781337553278Author:Raymond A. Serway, John W. JewettPublisher:Cengage Learning

Physics for Scientists and EngineersPhysicsISBN:9781337553278Author:Raymond A. Serway, John W. JewettPublisher:Cengage Learning Physics for Scientists and Engineers with Modern ...PhysicsISBN:9781337553292Author:Raymond A. Serway, John W. JewettPublisher:Cengage Learning

Physics for Scientists and Engineers with Modern ...PhysicsISBN:9781337553292Author:Raymond A. Serway, John W. JewettPublisher:Cengage Learning College PhysicsPhysicsISBN:9781938168000Author:Paul Peter Urone, Roger HinrichsPublisher:OpenStax College

College PhysicsPhysicsISBN:9781938168000Author:Paul Peter Urone, Roger HinrichsPublisher:OpenStax College