Concept explainers

Waves in the Earth and the Ocean

In December 2004, a large earthquake off the coast of Indonesia produced a devastating water wave, called a tsunami, that caused tremendous destruction thousands of miles away from the earthquake's epicenter. The tsunami was a dramatic illustration of the energy carried by waves.

It was also a call to action. Many of the communities hardest hit by the tsunami were struck hours after the waves were generated, long after seismic waves from the earthquake that passed through the earth had been detected al distant recording stations, long after the possibility of a tsunami was first discussed. With better detection and more accurate models of how a tsunami is formed and how a tsunami propagates, the affected communities could have received advance warning. The study of physics may seem an abstract undertaking with few practical applications, but on this day a better scientific understanding of these waves could have averted tragedy.

Let’s use our knowledge of waves to explore the properties of a tsunami. In Chapter 15, we saw that a vigorous shake of one end of a rope causes a pulse to travel

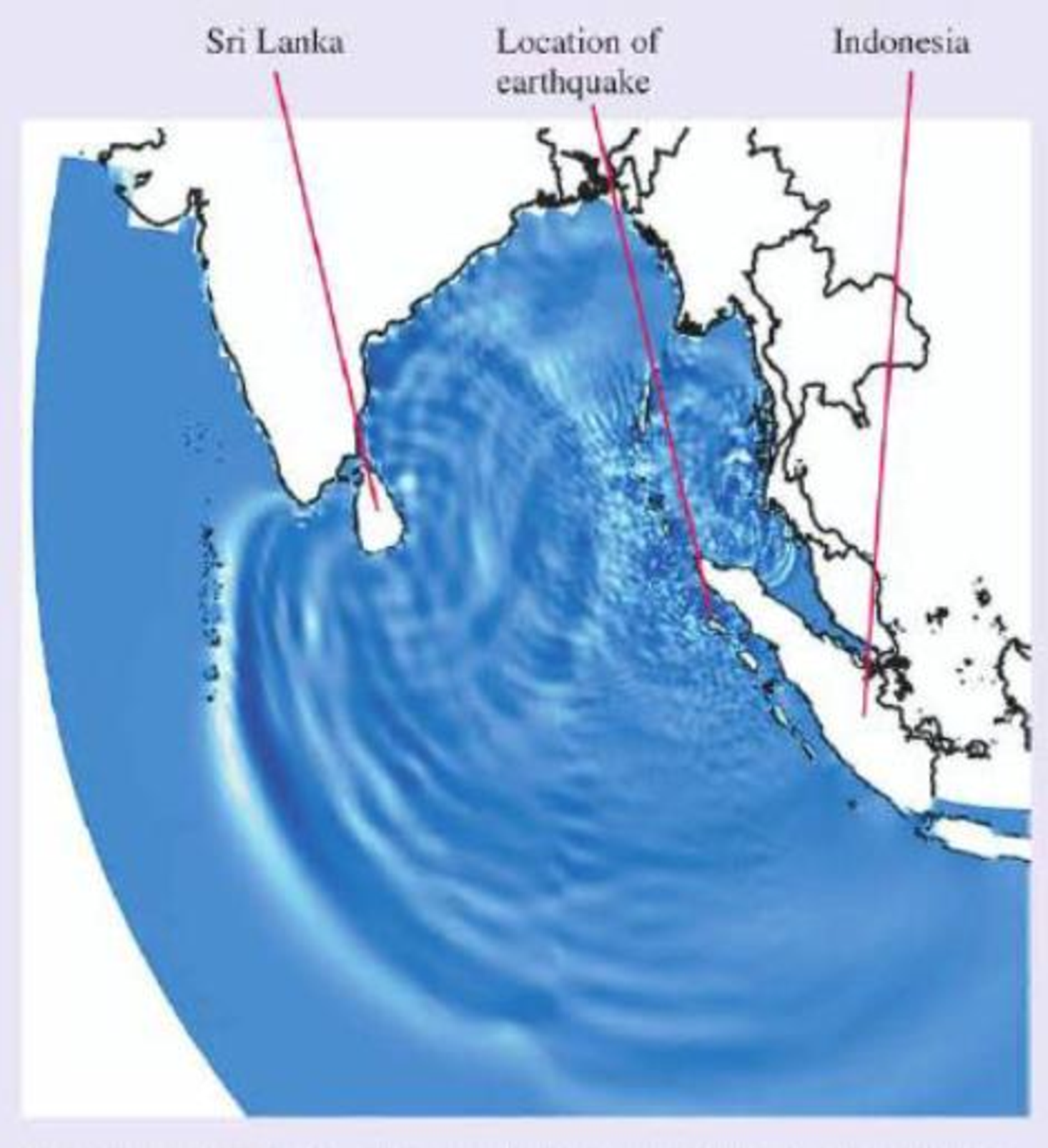

One frame from a computer simulation of the Indian Ocean tsunami three hours after the earthquake that produced it. The disturbance propagating outward from the earthquake is clearly seen, as are wave reflections from the island of Sri Lanka.

along it, carrying energy as it goes. The earthquake that produced the Indian Ocean tsunami of 2004 caused a sudden upward displacement of the seafloor that produced a corresponding rise in the surface of the ocean. This was the disturbance that produced the tsunami, very much like a quick shake on the end of a rope. The resulting wave propagated through the ocean, as we see in the figure.

This simulation of the tsunami looks much like the ripples that spread when you drop a pebble into a pond. But there is a big difference—the scale. The fact that you can see the individual waves on this diagram that spans 5000 km is quite revealing. To show up so clearly, the individual wave pulses must be very wide—up to hundreds of kilometers from front to back.

A tsunami is actually a “shallow water wave,” even in the deep ocean, because the depth of the ocean is much less than the width of the wave. Consequently, a tsunami travels differently than normal ocean waves. In Chapter 15 we learned that wave speeds are fixed by the properties of the medium. That is true for normal ocean waves, but the great width of the wave causes a tsunami to “feel the bottom.” Its wave speed is determined by the depth of the ocean: The greater the depth, the greater the speed. In the deep ocean, a tsunami travels at hundreds of kilometers per hour, much faster than a typical ocean wave. Near shore, as the ocean depth decreases, so docs the speed of the wave.

The height of the tsunami in the open ocean was about half a meter. Why should such a small wave—one that ships didn't even notice as it passed—be so fearsome? Again, it's the width of the wave that matters. Because a tsunami is the wave motion of a considerable mass of water, great energy is involved. As the front of a tsunami wave nears shore, its speed decreases, and the back of the wave moves faster than the front. Consequently, the width decreases. The water begins to pile up, and the wave dramatically increases in height.

The Indian Ocean tsunami had a height of up to 15 m when it reached shore, with a width of up to several kilometers. This tremendous mass of water was still moving at high speed, giving it a great deal of energy. A tsunami reaching the shore isn’t like a typical wave that breaks and crashes. It is a kilometers-wide wall of water that moves onto the shore and just keeps on coming. In many places, the water reached 2 km inland.

The impact of the Indian Ocean tsunami was devastating, but it was the first tsunami for which scientists were able to use satellites and ocean sensors to make planet-wide measurements. An analysis of the data has helped us better understand the physics of these ocean waves. We won’t be able to stop future tsunamis, but with a better knowledge of how they are formed and how they travel, we will be better able to warn people to get out of their way.

The following questions are related to the passage “Waves in the Earth and the Ocean” on the previous page.

The tsunami described in the passage produced a very erratic pattern of damage, with some areas seeing very large waves and nearby areas seeing only small waves. Which of the following is a possible explanation?

A. Certain areas saw the wave from the primary source, others only the reflected waves.

B. The superposition of waves from the primary source and reflected waves produced regions of constructive and destructive interference.

C. A tsunami is a standing wave, and certain locations were at nodal positions, others at antinodal positions.

Want to see the full answer?

Check out a sample textbook solution

Chapter P Solutions

College Physics: A Strategic Approach Technology Update, Books a la Carte Plus Mastering Physics with Pearson eText -- Access Card Package (3rd Edition)

Additional Science Textbook Solutions

Microbiology: An Introduction

Chemistry (7th Edition)

Organic Chemistry (8th Edition)

Anatomy & Physiology (6th Edition)

Applications and Investigations in Earth Science (9th Edition)

Human Physiology: An Integrated Approach (8th Edition)

- An infinitely long conducting cylindrical rod with a positive charge λ per unit length is surrounded by a conducting cylindrical shell (which is also infinitely long) with a charge per unit length of −2λ and radius r1, as shown in the figure. What is E(r), the radial component of the electric field between the rod and cylindrical shell as a function of the distance r from the axis of the cylindrical rod? Express your answer in terms of λ, r, and ϵ0, the permittivity of free space. What is σinner, the surface charge density (charge per unit area) on the inner surface of the conducting shell? What is σouterσouter, the surface charge density on the outside of the conducting shell? (Recall from the problem statement that the conducting shell has a total charge per unit length given by −2λ.) What is the radial component of the electric field, E(r), outside the shell?arrow_forwardA very long conducting tube (hollow cylinder) has inner radius aa and outer radius b. It carries charge per unit length +α, where αα is a positive constant with units of C/m. A line of charge lies along the axis of the tube. The line of charge has charge per unit length +α. Calculate the electric field in terms of α and the distance r from the axis of the tube for r<a. Calculate the electric field in terms of α and the distance rr from the axis of the tube for a<r<b. Calculate the electric field in terms of αα and the distance r from the axis of the tube for r>b. What is the charge per unit length on the inner surface of the tube? What is the charge per unit length on the outer surface of the tube?arrow_forwardTwo small insulating spheres with radius 9.00×10−2 m are separated by a large center-to-center distance of 0.545 m . One sphere is negatively charged, with net charge -1.75 μC , and the other sphere is positively charged, with net charge 3.70 μC . The charge is uniformly distributed within the volume of each sphere. What is the magnitude E of the electric field midway between the spheres? Take the permittivity of free space to be ϵ0 = 8.85×10−12 C2/(N⋅m2) . What is the direction of the electric field midway between the spheres?arrow_forward

- A conducting spherical shell with inner radius aa and outer radius bb has a positive point charge Q located at its center. The total charge on the shell is -3Q, and it is insulated from its surroundings. Derive the expression for the electric field magnitude in terms of the distance r from the center for the region r<a. Express your answer in terms of some or all of the variables Q, a, b, and appropriate constants. Derive the expression for the electric field magnitude in terms of the distance rr from the center for the region a<r<b. Derive the expression for the electric field magnitude in terms of the distance rr from the center for the region r>b. What is the surface charge density on the inner surface of the conducting shell? What is the surface charge density on the outer surface of the conducting shell?arrow_forwardA small sphere with a mass of 3.00×10−3 g and carrying a charge of 4.80×10−8 C hangs from a thread near a very large, charged insulating sheet, as shown in the figure (Figure 1). The charge density on the sheet is −2.20×10−9 C/m2 . Find the angle of the thread.arrow_forwardA small conducting spherical shell with inner radius aa and outer radius bb is concentric with a larger conducting spherical shell with inner radius c and outer radius d (Figure 1). The inner shell has total charge +2q, and the outer shell has charge −2q. Calculate the magnitude of the electric field in terms of q and the distance rr from the common center of the two shells for r<a. Calculate the magnitude of the electric field for a<r<b. Calculate the magnitude of the electric field for b<r<c.arrow_forward

- A cube has sides of length L = 0.800 m . It is placed with one corner at the origin as shown in the figure. The electric field is not uniform but is given by E→=αxi^+βzk^, where α=−3.90 and β= 7.10. What is the sum of the flux through the surface S5 and S6? What is the sum of the flux through the surface S2 and S4? Find the total electric charge inside the cube.arrow_forwardIn the figure, a proton is projected horizontally midway between two parallel plates that are separated by 0.6 cm. The electrical field due to the plates has magnitude 450000 N/C between the plates away from the edges. If the plates are 3 cm long, find the minimum speed of the proton if it just misses the lower plate as it emerges from the field.arrow_forwardA point charge of magnitude q is at the center of a cube with sides of length L. What is the electric flux Φ through each of the six faces of the cube? What would be the flux Φ1 through a face of the cube if its sides were of length L1? Please explain everything.arrow_forward

- If a 1/2 inch diameter drill bit spins at 3000 rotations per minute, how fast is the outer edge moving as it contacts a piece of metal while drilling a machine part?arrow_forwardNeed help with the third question (C)A gymnast weighing 68 kg attempts a handstand using only one arm. He plants his hand at an angl reesulting in the reaction force shown.arrow_forwardQ: What is the direction of the force on the current carrying conductor in the magnetic field in each of the cases 1 to 8 shown below? (1) B B B into page X X X x X X X X (2) B 11 -10° B x I B I out of page (3) I into page (4) B out of page out of page I N N S x X X X I X X X X I (5) (6) (7) (8) Sarrow_forward

Physics for Scientists and Engineers, Technology ...PhysicsISBN:9781305116399Author:Raymond A. Serway, John W. JewettPublisher:Cengage Learning

Physics for Scientists and Engineers, Technology ...PhysicsISBN:9781305116399Author:Raymond A. Serway, John W. JewettPublisher:Cengage Learning College PhysicsPhysicsISBN:9781938168000Author:Paul Peter Urone, Roger HinrichsPublisher:OpenStax College

College PhysicsPhysicsISBN:9781938168000Author:Paul Peter Urone, Roger HinrichsPublisher:OpenStax College An Introduction to Physical SciencePhysicsISBN:9781305079137Author:James Shipman, Jerry D. Wilson, Charles A. Higgins, Omar TorresPublisher:Cengage Learning

An Introduction to Physical SciencePhysicsISBN:9781305079137Author:James Shipman, Jerry D. Wilson, Charles A. Higgins, Omar TorresPublisher:Cengage Learning Principles of Physics: A Calculus-Based TextPhysicsISBN:9781133104261Author:Raymond A. Serway, John W. JewettPublisher:Cengage Learning

Principles of Physics: A Calculus-Based TextPhysicsISBN:9781133104261Author:Raymond A. Serway, John W. JewettPublisher:Cengage Learning Glencoe Physics: Principles and Problems, Student...PhysicsISBN:9780078807213Author:Paul W. ZitzewitzPublisher:Glencoe/McGraw-Hill

Glencoe Physics: Principles and Problems, Student...PhysicsISBN:9780078807213Author:Paul W. ZitzewitzPublisher:Glencoe/McGraw-Hill Physics for Scientists and Engineers: Foundations...PhysicsISBN:9781133939146Author:Katz, Debora M.Publisher:Cengage Learning

Physics for Scientists and Engineers: Foundations...PhysicsISBN:9781133939146Author:Katz, Debora M.Publisher:Cengage Learning