Concept explainers

Size and Life

Physicists look for simple models and general principles that underlie and explain diverse physical phenomena. In the first 13 chapters of this textbook, you’ve seen that just a handful of general principles and laws can be used to solve a wide range of problems. Can this approach have any relevance to a subject like biology? It may seem surprising, but there are general 'laws of biology“’ that apply, with quantitative accuracy, to organisms as diverse as elephants and mice.

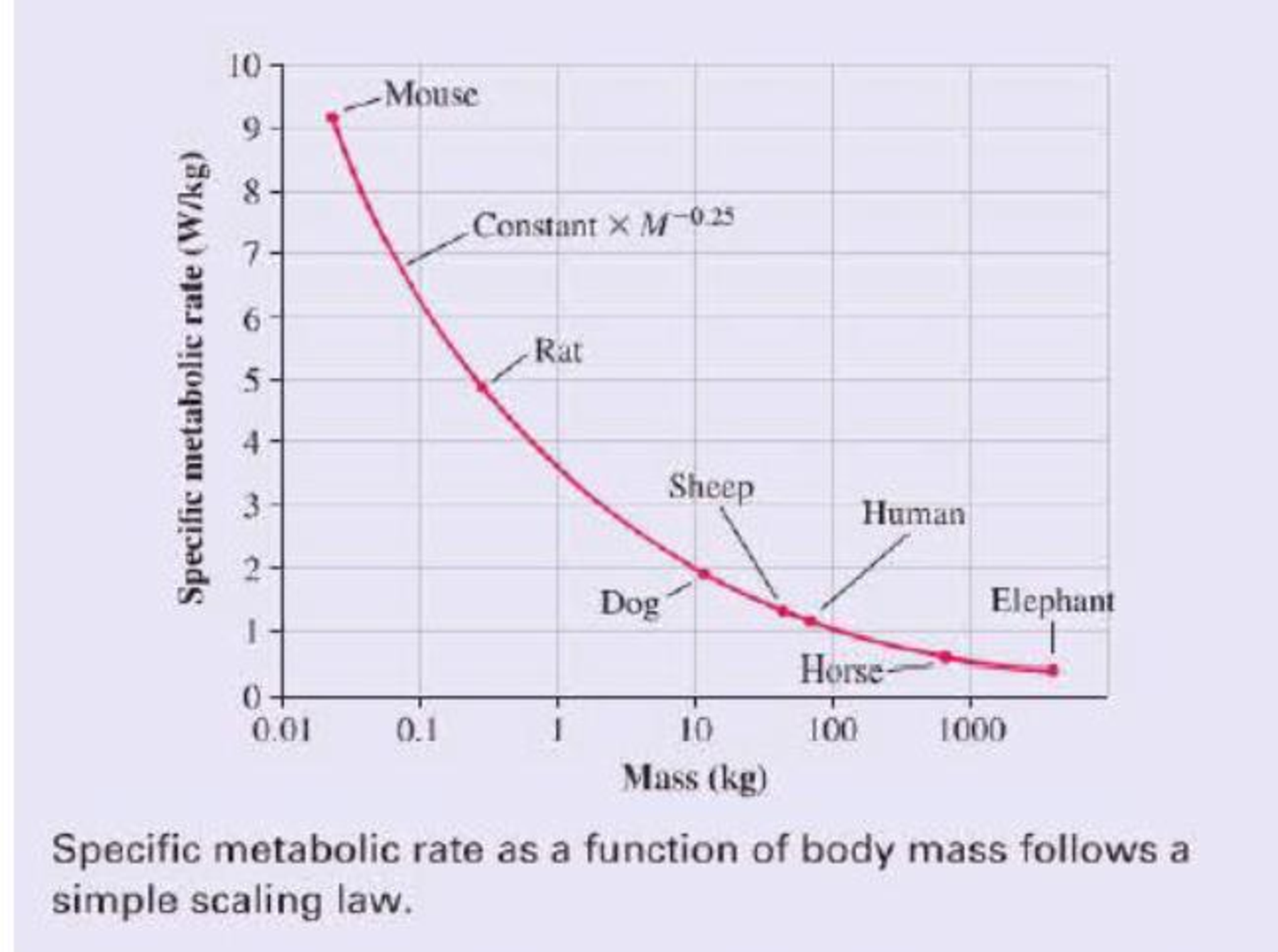

Let’s look at an example. An elephant uses more metabolic power than a mouse. This is not surprising, as an elephant is much bigger. But recasting the data shows an interesting trend. When we looked at the energy required to raise the temperature of different substances, we considered specific heat. The “specific” meant that we considered the heat required for 1 kilogram. For animals, rather than metabolic rate, we can look at the specific metabolic rate, the metabolic power used per kilogram of tissue. If we factor out the mass difference between a mouse and an elephant, are their specific metabolic powers the same?

In fact, the specific metabolic rate varies quite a bit among mammals, as the graph of specific metabolic rate versus mass shows. But there is an interesting trend: All of the data points lie on a single smooth curve. In other words, there really is a biological law we can use to predict a mammal’s metabolic rate knowing only its mass M. In particular, the specific metabolic rate is proportional to M –0.25. Because a 4000 kg elephant is 160,000 times more massive than a 25 g mouse, the mouse’s specific metabolic power is (160,000)0.25 = 20 times that of the elephant. A law that shows how a property scales with the size of a system is called a scaling law.

A similar scaling law holds for birds, reptiles, and even bacteria. Why should a single simple relationship hold true for organisms that range in size from a single cell to a 100 ton blue whale? Interestingly, no one knows for sure. It is a matter of current research to find out just what this and other scaling laws tell us about the nature of life.

Perhaps the metabolic-power scaling law is a result of

If heat dissipation were the only factor limiting metabolism, we can show that the specific metabolic rate should scale as M–0.33quite different from the M–0.25 scaling observed. Clearly, another factor is at work. Exactly what underlies the M–0.25 scaling is still a matter of debate, but some recent analysis suggests the scaling is due to limitations not of heat transfer but of fluid flow. Cells in mice, elephants, and all mammals receive nutrients and oxygen for metabolism from the bloodstream. Because the minimum size of a capillary is about the same for all mammals, the structure of the circulatory system must vary from animal to animal. The human aorta has a diameter of about 1 inch; in a mouse, the diameter is approximately l/20th of this. Thus a mouse has fewer levels of branching to smaller and smaller blood vessels as we move from the aorta to the capillaries. The smaller blood vessels in mice mean that viscosity is more of a factor throughout the circulatory system. The circulatory system of a mouse is quite different from that of ail elephant.

A model of specific metabolic rate based on blood-flow limitations predicts a M–0.25 law, exactly as observed. The model also makes other testable predictions. For example, the model predicts that the smallest possible mammal should have a body mass of about 1 gram—exactly the size of the smallest shrew. Even smaller animals have different types of circulatory' systems; in the smallest animals, nutrient transport is by diffusion alone. But the model can be extended to predict that the specific metabolic rate for these animals will follow a scaling law similar to that for mammals, exactly as observed. It is too soon to know if this model will ultimately prove to be correct, but it’s indisputable that there are large-scale regularities in biology that follow mathematical relationships based on the laws of physics.

The following questions are related to the passage "Size and Life" on the previous page.

Given the data of the graph, approximately how much energy, in Calories, would a 200 g rat use during the course of a day?

- A. 10

- B. 20

- C. 100

- D. 200

Want to see the full answer?

Check out a sample textbook solution

Chapter P Solutions

College Physics: A Strategic Approach Technology Update, Books a la Carte Plus Mastering Physics with Pearson eText -- Access Card Package (3rd Edition)

Additional Science Textbook Solutions

Cosmic Perspective Fundamentals

Campbell Biology in Focus (2nd Edition)

Campbell Biology: Concepts & Connections (9th Edition)

Chemistry: An Introduction to General, Organic, and Biological Chemistry (13th Edition)

Campbell Essential Biology with Physiology (5th Edition)

Chemistry: A Molecular Approach (4th Edition)

- The car goes from driving straight to spinning at 10.6 rev/min in 0.257 s with a radius of 12.2 m. The angular accleration is 4.28 rad/s^2. During this flip Barbie stays firmly seated in the car’s seat. Barbie has a mass of 58.0 kg, what is her normal force at the top of the loop?arrow_forwardConsider a hoop of radius R and mass M rolling without slipping. Which form of kinetic energy is larger, translational or rotational?arrow_forwardA roller-coaster vehicle has a mass of 571 kg when fully loaded with passengers (see figure). A) If the vehicle has a speed of 22.5 m/s at point A, what is the force of the track on the vehicle at this point? B) What is the maximum speed the vehicle can have at point B, in order for gravity to hold it on the track?arrow_forward

- This one wheeled motorcycle’s wheel maximum angular velocity was about 430 rev/min. Given that it’s radius was 0.920 m, what was the largest linear velocity of the monowheel?The monowheel could not accelerate fast or the rider would start spinning inside (this is called "gerbiling"). The maximum angular acceleration was 10.9 rad/s2. How long, in seconds, would it take it to hit maximum speed from rest?arrow_forwardIf points a and b are connected by a wire with negligible resistance, find the magnitude of the current in the 12.0 V battery.arrow_forwardConsider the two pucks shown in the figure. As they move towards each other, the momentum of each puck is equal in magnitude and opposite in direction. Given that v kinetic energy of the system is converted to internal energy? 30.0° 130.0 = green 11.0 m/s, and m blue is 25.0% greater than m 'green' what are the final speeds of each puck (in m/s), if 1½-½ t thearrow_forward

- Consider the blocks on the curved ramp as seen in the figure. The blocks have masses m₁ = 2.00 kg and m₂ = 3.60 kg, and are initially at rest. The blocks are allowed to slide down the ramp and they then undergo a head-on, elastic collision on the flat portion. Determine the heights (in m) to which m₁ and m2 rise on the curved portion of the ramp after the collision. Assume the ramp is frictionless, and h 4.40 m. m2 = m₁ m hm1 hm2 m iarrow_forwardA 3.04-kg steel ball strikes a massive wall at 10.0 m/s at an angle of 0 = 60.0° with the plane of the wall. It bounces off the wall with the same speed and angle (see the figure below). If the ball is in contact with the wall for 0.234 s, what is the average force exerted by the wall on the ball? magnitude direction ---Select--- ✓ N xarrow_forwardYou are in the early stages of an internship at NASA. Your supervisor has asked you to analyze emergency procedures for extravehicular activity (EVA), when the astronauts leave the International Space Station (ISS) to do repairs to its exterior or perform other tasks. In particular, the scenario you are studying is a failure of the manned-maneuvering unit (MMU), which is a nitrogen-propelled backpack that attaches to the astronaut's primary life support system (PLSS). In this scenario, the astronaut is floating directly away from the ISS and cannot use the failed MMU to get back. Therefore, the emergency plan is to take off the MMU and throw it in a direction directly away from the ISS, an action that will hopefully cause the astronaut to reverse direction and float back to the station. You have the following mass data provided to you: astronaut: 78.1 kg, spacesuit: 36.8 kg, MMU: 115 kg, PLSS: 145 kg. Based on tests performed by astronauts floating "weightless" inside the ISS, the most…arrow_forward

- Three carts of masses m₁ = 4.50 kg, m₂ = 10.50 kg, and m3 = 3.00 kg move on a frictionless, horizontal track with speeds of V1 v1 13 m 12 mq m3 (a) Find the final velocity of the train of three carts. magnitude direction m/s |---Select--- ☑ (b) Does your answer require that all the carts collide and stick together at the same moment? ○ Yes Ο Νο = 6.00 m/s to the right, v₂ = 3.00 m/s to the right, and V3 = 6.00 m/s to the left, as shown below. Velcro couplers make the carts stick together after colliding.arrow_forwardA girl launches a toy rocket from the ground. The engine experiences an average thrust of 5.26 N. The mass of the engine plus fuel before liftoff is 25.4 g, which includes fuel mass of 12.7 g. The engine fires for a total of 1.90 s. (Assume all the fuel is consumed.) (a) Calculate the average exhaust speed of the engine (in m/s). m/s (b) This engine is positioned in a rocket body of mass 70.0 g. What is the magnitude of the final velocity of the rocket (in m/s) if it were to be fired from rest in outer space with the same amount of fuel? Assume the fuel burns at a constant rate. m/sarrow_forwardTwo objects of masses m₁ 0.48 kg and m₂ = 0.86 kg are placed on a horizontal frictionless surface and a compressed spring of force constant k 260 N/m is placed between them as in figure (a). Neglect the mass of the spring. The spring is not attached to either object and is compressed a distance of 9.4 cm. If the objects are released from rest, find the final velocity of each object as shown in figure (b). (Let the positive direction be to the right. Indicate the direction with the sign of your answer.) m/s V1 V2= m1 m/s k m2 a す。 k m2 m1 barrow_forward

Physics for Scientists and Engineers: Foundations...PhysicsISBN:9781133939146Author:Katz, Debora M.Publisher:Cengage Learning

Physics for Scientists and Engineers: Foundations...PhysicsISBN:9781133939146Author:Katz, Debora M.Publisher:Cengage Learning University Physics Volume 1PhysicsISBN:9781938168277Author:William Moebs, Samuel J. Ling, Jeff SannyPublisher:OpenStax - Rice University

University Physics Volume 1PhysicsISBN:9781938168277Author:William Moebs, Samuel J. Ling, Jeff SannyPublisher:OpenStax - Rice University Physics for Scientists and Engineers, Technology ...PhysicsISBN:9781305116399Author:Raymond A. Serway, John W. JewettPublisher:Cengage Learning

Physics for Scientists and Engineers, Technology ...PhysicsISBN:9781305116399Author:Raymond A. Serway, John W. JewettPublisher:Cengage Learning Physics for Scientists and EngineersPhysicsISBN:9781337553278Author:Raymond A. Serway, John W. JewettPublisher:Cengage Learning

Physics for Scientists and EngineersPhysicsISBN:9781337553278Author:Raymond A. Serway, John W. JewettPublisher:Cengage Learning Physics for Scientists and Engineers with Modern ...PhysicsISBN:9781337553292Author:Raymond A. Serway, John W. JewettPublisher:Cengage Learning

Physics for Scientists and Engineers with Modern ...PhysicsISBN:9781337553292Author:Raymond A. Serway, John W. JewettPublisher:Cengage Learning College PhysicsPhysicsISBN:9781938168000Author:Paul Peter Urone, Roger HinrichsPublisher:OpenStax College

College PhysicsPhysicsISBN:9781938168000Author:Paul Peter Urone, Roger HinrichsPublisher:OpenStax College